Night’s Master by Tanith Lee (1978)

8/10

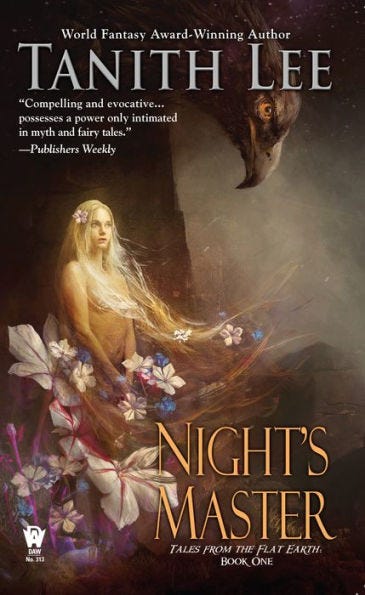

Edition: I read the 2015 DAW Books reissue on Kindle, although I’d much prefer the mass market paperback with Edmund Duke’s cover art—there’s an orange mosque cityscape with large white embellished text in the foreground, a thing that evokes burning deserts and cold mirages. . . True beauty for the shelves. Alas, the price. . .

I wasn’t going to read this book. I was trying, in fact, to begin Lord Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter. Before I got started, however, I downloaded a few Kindle samples of other fantasy books recommended in a recent Bookpilled YouTube video. I burned through the sample of Night’s Master, moved on to the book proper, and was finished almost before I realized I had gotten off track.

This is my first Lee, and it will not be my last. It’s one of those books that managed to change my perception of an entire genre—fantasy, in this case. Not that I had anything against fantasy. I just didn’t know it could be this intensely seductive, thoughtful, gorgeous. . . unless, of course, Rikki Ducornet counts as fantasy (I’m calling it: she does.).

Night’s Master is the first novel in Lee’s Tales of the Flat Earth series—which, don’t worry, has nothing to do with that flat Earth. Here it’s more of a metaphysical construct in her worldbuilding—or, as I’d rather think of it, an anti-metaphysical construct. I’ll explain what I mean in a second, but first I need to point out that the term “novel” is complicated here by the fact that the book is written as a series of interconnected short stories rather than a single, continuous narrative. This proves a stunningly versatile form in Lee’s hands, and we move across the geography of the flat Earth at ease as the narrative thumbs through the life of multiple characters in various circumstances. The view is panoramic, but also, always principally humane. We aren’t simply taking in sights of an imaginary world (though sights there are—deliciously strange ones) but traveling across a variegated spectrum of human experiences.

This also has something to do with the novel’s anti-metaphysics. Let’s get to that. The flat Earth is built in a tripartite fashion: There is what is simply called the Earth, corresponding to our everyday, phenomenal realm; there is the “underearth,” roughly analogous to Hell, but also related physically to the world of dreams; and of course there must be “overearth,” which is heaven, but a strange, remote, even surreal landscape of frozen gods that oddly reminds me of the album art of Macintosh Plus’ Floral Shoppe. By the way, the brief sequence in heaven is one of my favorite parts of this book.

What Lee gains with this structure is simplicity. An emanationist metaphysics of different levels nested within concentric spheres is ideal for accounting for the fallen state of materiality and mapping states of spiritual ascension, but rather on the sluggish side when it comes to rapid movements from one level to the next. Taking her cue from Dante, the master of the three-realm travelogue, Lee presents a stage rather than a cosmos. All the panels are wide open, easy to imagine, apprehend, and traverse. And there, in the middle of it all is her principal character: Azhrarn, who is Satan, but a Miltonic one. That is, a charmer, a scamp, a Byronic hero, but not a hero to the extent that he is prevented from being truly, tremendously cruel.

It’s easy to overemphasize the importance of form when tracing the movements of a narrative: its exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution—these aspects are visible, intuitive and logical—but of equal importance is formlessness. In a work of art, what gives narrative forms life, or texture, is what I call the “locus of distortion,” that is, an uncontrollable principle or point of attraction that distorts everything that falls into it, like the twisting motion around a drain, or the distortions of time and space around a black hole. This is what gives a work of art its inscrutable logic, its quality of being “based on unknown and hence unquestionable rules,” to quote a character in Pasolini’s film, Teorema (1968). Azhrarm is this locus of distortion, and like the otherworldly “Visitor” in Teorema, he wields a power of seduction that humans find irresistible. This power is so strong that the lives of his lovers are withered and empty when his affections are withdrawn, but Azhrarm uses this power lightly, like a child (and what are gods if not children, in some strange way?) leaving a path of destruction and suffering behind him.

Azhrarm destroys who he is finished with, who spurns him, or simply who is in the wrong place at the wrong time. He is wholly beyond good and evil—in short, a beautiful machine that reenacts the vagrant destinies of life. As such, prosperity never gets ahead of ruin, but neither does ruin ever fully prevail. What occurs on the three-part stage of Night’s Master is a play of opposites. Much like the traditional folkloric tales that Lee derives considerable inspiration from, the texture of this book is more seasonal than moral—everything is coming-into-being both despite and due to Azhrarm’s trickster-like wiles. That is, this is a book firmly in the realm of true magic—one that might prove a needed antidote for the overwhelming Spirit of the Times, but that’s a whole new dimension of consideration that I’ll end here.

I heartily recommend Night’s Master. An easy read, but often florid, frequently delightful, and very rarely tedious.

Rating: 8/10